Virtual coffee with photographer Fernando Gallegos

This is the first of our virtual coffee interview series, a deep dive into the mind of Fernando Gallegos, a photographer and photobook editor from Monterrey, Mexico. Pour a cup of your favorite warm drink and enjoy this 5-10 minute read.

Fernando, your artistic journey began with a focus on photography and has evolved into editing and designing photobooks. Can you share some insights into how this transition happened and how it has influenced your career?

Fernando: I am a very curious person; my main interest has always been in how things work. With photography, it was no different. During my training and early years as an artist, my focus was on seeing everything I could from other artists and doing everything I could think of to then evaluate and study what worked and what didn't. At one point in my career, other artists began to show me their work for feedback, which evolved from casual advice to consulting and mentoring, while I immersed myself more and more in the world of photobooks along with other colleagues. Although I don't plan to abandon my practice as an artist, in recent years my work has leaned towards the academic side of photography and art. The conceptual design of photobooks is a kind of laboratory for me from which I can test some ideas and even develop theories about the language of photography as a narrative medium.

Throughout your career, you have explored photography as a narrative medium. Can you discuss the key elements you consider when constructing a visual story?

Fernando: Photography is read through our notion of what we consider "real." In other words, we read a photograph using our memory, what we see awakens aesthetic responses in us that become sensory fragments of things we have experienced before. Taking this into account, when constructing a photographic narrative, I try to turn each image into a fragment of a story that exists behind the images and that functions as an invisible link between each image selected for the narrative. What I seek is for the viewer to feel as if they are remembering having lived the situation presented in the photographic work, thus putting the viewer in a position to confront these narratives as if they were real, as if they had happened to them before. In short, a photographic narrative must be presented as the possibility of a reality, even when that "possible reality" is a construction or fiction created by the artist.

You have worked extensively with photographer Alejandro Cartagena on several acclaimed photobooks. How did this collaboration begin, and how has your professional relationship evolved over the years?

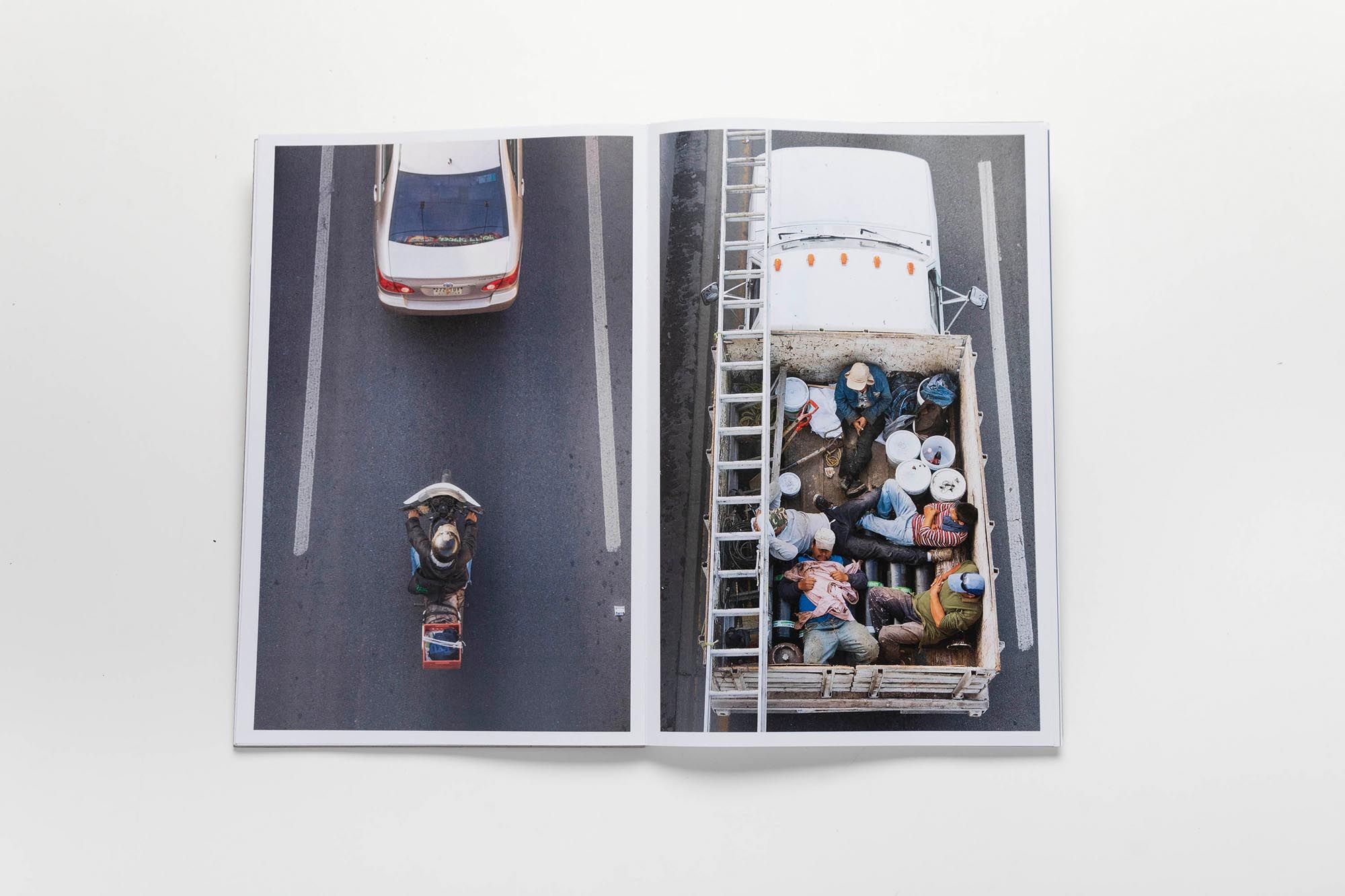

Fernando: I met Alejandro at university where I took one of his classes, and after that, I assisted him in his studio for a while. During the photobook boom of the 2010s, we both became very excited about the possibilities that this format offered for photographic narrative work. Alejandro began collecting photobooks around that time, and we spent hours talking and thinking about them. When Alejandro decided to publish a book of his work, Carpoolers, he invited me to brainstorm with him on how the book could be, and that's where our collaboration of over 10 years began. Usually, Alejandro presents me with a completed photographic project and crazy ideas for a book, and my job has been the traditional work of an editor: grounding the idea, developing the book concept, editing and sequencing the work, and proposing the final output. Later on, we began working on book proposals for other artists, with Alejandro acting as the book's producer while I took care of most of the conceptual and language work as a photobook editor/designer. Currently, both of us are fully immersed in the world of web3 and its possibilities for photography, although I continue to work on photobook projects, currently working simultaneously on three new books.

As an artist, you have participated in several group exhibitions in multiple countries. Can you share some memorable experiences or insights from these exhibitions?

Fernando: The best part of participating in these exhibitions is getting to know new people and places. With their obvious differences, the experience is not very different from what we experienced last year with the boom in photography NFTs. You meet people, experiment, and exchange ideas with them, creating a strange bond of brotherhood that stays with you for a while. Some of the best memories I have are from exhibiting at a festival called alt+1000 in Switzerland, alongside some Mexican colleagues and other international artists. I will never forget attending a party at Balthus' (the painter) house for his daughter's birthday, where Kylie Minogue sang happy birthday, and some of my colleagues danced with Wim Wenders.

Your work has been shortlisted for prestigious photography festivals such as the Aperture Foundation Photobook Award and Les Recontres d'Arles. How have these recognitions influenced your approach to photography and photobook design?

Fernando: I think many people who are dedicated to photography and theorizing about it live in constant doubt about whether what they are doing is correct, whether it works, whether it is understood, whether it is worth it... The recognition of the work I have done over the last 15 years always presents itself to me as confirmation of the ideas I have developed during that time. Recently, a book I designed, edited, and sequenced for Alejandro Cartagena (A Small Guide to Home-Ownership) was selected for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2021, an award that goes beyond just the photobook format. This makes me understand that what we do goes beyond a language contained in a book; we are using the book as a space where a curatorial proposal can be generated and integrated as a form of presentation for the language of photography itself. Curiously, any recognition of my work helps me confirm that each project presents entirely different challenges, and there is no single way to solve those challenges. In a way, recognition tells me that the most important thing in a photographic project is to try to deeply understand how the body of work speaks so that we can communicate it to others.

In recent years, you have been exploring web3 organizations and new ways to publish photography. Can you explain your interest in this area and how you think it will shape the future of photography and photobook design?

Fernando: The concept of web3 gives a kind of solidity to the digital space. I see it as an attempt to delimit an area in which art and photography can be presented. And if we can delimit that area, then we can use it to present photography. As long as that delimited space exists, curatorial possibilities exist. A photobook, for example, is a curatorial proposal for a book format, and my interest at the moment is in finding that type of proposal in the web3 space. The problem is that this space is still in formation; sometimes it feels solid and consistent, but at other times it seems to dissolve into noise and possibilities rather than facts. The challenge is great; we are talking about a space that seems to have no limits and is constantly changing. Efforts to contain attention and focus on a specific part of Web3 become more complicated as technology advances in a space that fosters innovation to such an extent. On the other hand, we have the opportunity to understand digital photography as a natural form of the medium instead of a digital copy of a physical work, as it was until very recently. As we understand that a photograph can be an original piece as a digital work, the true transformation of language for the medium of photography will present itself to us. Another interesting aspect is the use of emerging technologies such as the creation/modification of photographs or photographic images through artificial intelligence, where the tool itself poses conceptual challenges and new narrative forms that we are only beginning to discover. In summary, I believe that Web3 is currently presented to us as a great laboratory for understanding photography as a digital image and our relationship with photographic art as a narrative form.

In addition to your artistic activities, you have a small café and photobook store in Monterrey. How has this business impacted your connection with the local community and the art world in general?

Fernando: Artistic activity in Monterrey, compared to many other parts of the world, is practically nonexistent. There is a very small circuit of artists producing work that is exhibited in a very small number of galleries in the city. This is problematic for innovation in artistic proposals and even for the diversity of ideas. Opening a photobook store in a city like this was the challenge that awaited me for a niche product worldwide. I want this store to be a kind of oasis that anyone interested in photography can come to and spend time looking at the work of artists from around the world, and although I probably haven't seen much change in that aspect for this specific community, it's a store that I would have liked to have access to when I was a student and that I believe any photography enthusiast can appreciate. On the other hand, being a specialty coffee shop as well, we have a high flow of people, some of whom end up finding something they probably didn't expect in a photobook, and hopefully, the seed of interest in photography is planted in some of them.

As an educator, you have taught several workshops on photography and photobook editing. What do you enjoy most about teaching, and how has it influenced your own artistic practice?

Fernando: Teaching is an opportunity for me to reinforce some of my ideas. Trying to organize them in a way that is clear to students helps me better understand some of the approaches I have developed over time. Inevitably, reinforcing my ideas strengthens my artistic goals, and in that way, new conceptual and formal possibilities open up that I apply in my practice.

You have received numerous scholarships and awards throughout your career. How have these opportunities helped you grow as an artist and support your various projects?

Fernando: The last few years immersed in Web3 made me realize how difficult it is to live off art in a country like Mexico. Artworks are rarely sold; much of my income came from consultations and my position at the university. Having second and third jobs is a normal practice for artists in Mexico. For the last 10 years, I have been fortunate to have been a beneficiary of grants for artistic production consistently, something that has helped me focus on my work as an artist, curator, and photography thinker. These last 2 years, the sale of NFTs has helped me similarly, allowing me to think, develop theory, and share it in the context of NFTs. Simply having a secure income specifically for art production is enormous for the development of any artist.

Looking to the future, are there specific themes, techniques, or collaborations that you hope to explore in your future work? How do you imagine the ongoing evolution of your artistic practice?

Fernando: My work has always been somewhat silent. I explore language as something that is part of life, not as something disruptive; I try to make my work flow at the same pace as my daily experience. For that reason, I hope that my work continues to reflect that silent contemplation of what surrounds me, but hopefully, I can continue integrating what I learn as tools that continue to be developed thanks to Web3 become integrated into the general artistic practice of my generation. Although I don't have a specific collaboration in mind, I have made a point in this space to experiment with different formats and methods of publication. I understand that it is a time of innovation and discovery, so I want to experiment with everything I can in an effort to understand new forms for the language to which I have dedicated my life.